Addressing the Economic Calculation Problem and Building Socialism in the Modern Era

A Critical Marxist Article

Introduction: Why the Economic Calculation Problem Still Matters

When Ludwig von Mises first formulated the Economic Calculation Problem (ECP) in 1920, he sought to prove not merely that socialism was inefficient but that it was impossible. His argument was deceptively simple: without private ownership of the means of production, there can be no genuine market exchange; without exchange, there can be no prices; and without prices, there can be no rational way to compare the costs and benefits of different production decisions. To build a railway through a mountain or around it, to allocate steel to tractors or turbines, to decide whether one plan is more efficient than another, all such choices require a common unit of measurement. According to Mises, capitalism had discovered that unit in prices, and socialism, by abolishing markets, condemned itself to irrationality.

For over a century, defenders of capitalism have wielded this argument as a bludgeon against socialism. It was reinforced and expanded by Friedrich Hayek, who argued that the dispersed and tacit knowledge of individuals could never be centralized. Markets, for him, were not just mechanisms of exchange but epistemological systems, the only way human beings could coordinate knowledge too vast for any planner to comprehend. Together, Mises and Hayek built a theoretical edifice that declared the socialist project doomed before it began.

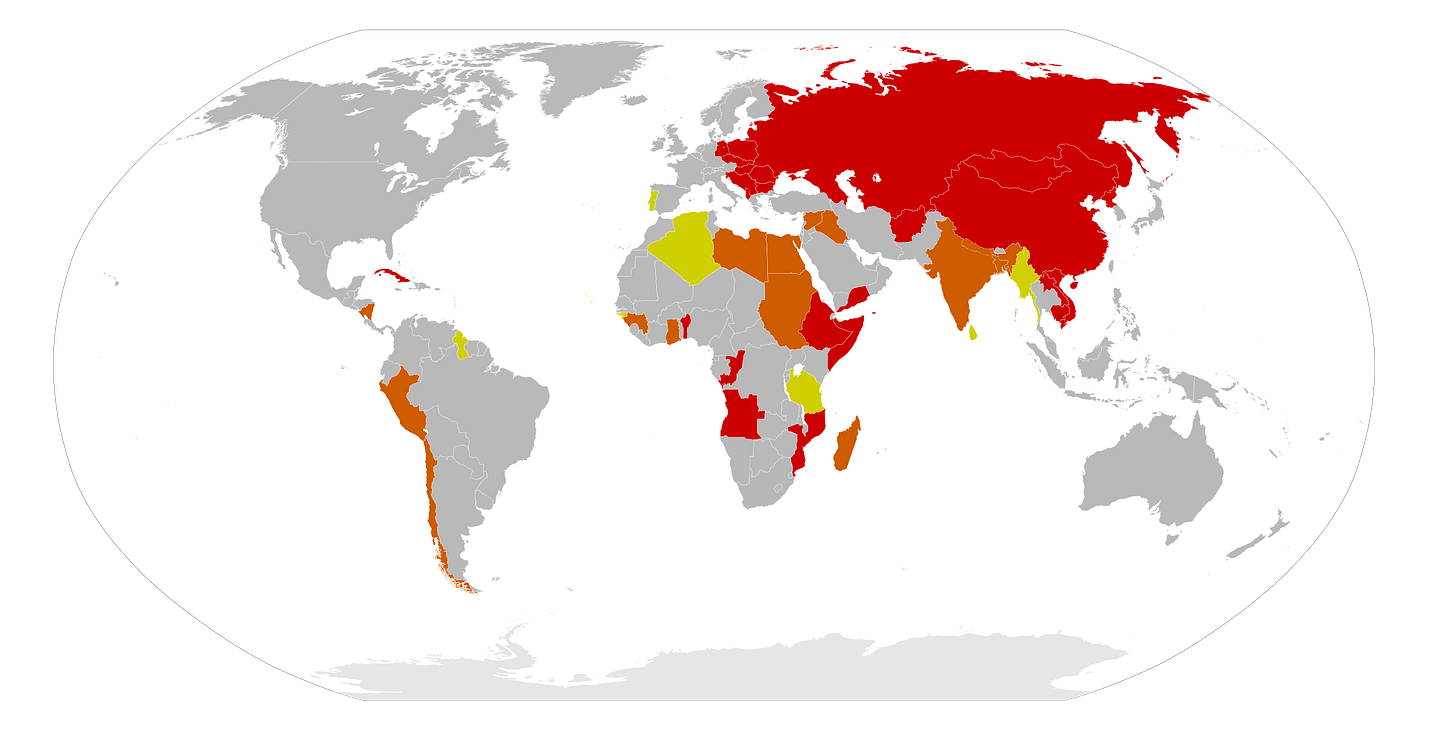

Yet history complicates theory. The Soviet Union industrialized at unprecedented speed, defeated Nazi Germany, and put the first human into space, all under planning. China, despite its shifts and contradictions, has lifted hundreds of millions out of poverty through a “socialist market economy.” Meanwhile, capitalism itself continues to produce crises of irrationality: speculative bubbles, mass unemployment, and ecological destruction. If markets are supposed to guarantee rational allocation, how do we explain the financial crash of 2008, the millions of empty houses alongside millions of homeless, or the vast waste of overproduction while billions remain hungry?

The paradox is clear: the ECP points to a real difficulty that socialism must take seriously, but it does not prove socialism impossible. The question is not whether calculation can be done without private markets; the answer is yes, as even wartime economies demonstrate, but how it can be done in a socialist manner that overcomes alienation, hierarchy, and waste. What Mises mistook for an eternal truth of markets was, in fact, only a temporary expression of a deeper reality: that all value ultimately rests on socially necessary labor time. Prices under capitalism are but distorted signals of that labor, shaped by exploitation and competition. Socialist planning, to succeed, must build calculation on this foundation directly.

The collapse of many 20th-century socialist states shows what happens when this problem is not solved. The Soviet Union, for example, attempted to fix prices administratively, but without tying them to real labor inputs or material coefficients. The result was a system of fictitious prices, disconnected from the actual costs of production, which led to misallocation and waste. Mises was right to say Soviet planners were “groping in the dark,” but wrong to imagine that darkness is inevitable. The lesson is not that socialism is doomed, but that socialism must develop new methods of calculation, methods that retain the rationality markets approximate while surpassing them in transparency, equity, and ecological responsibility.

Today, with the tools of cybernetics, real-time data, artificial intelligence, and global digital infrastructure, socialism has resources at its disposal that Marx, Mises, or even Deng Xiaoping could not have imagined. We stand at a turning point where the ECP can no longer be wielded as a fatalistic objection but must be understood as a dialectical contradiction, one that compels innovation, synthesis, and revolutionary creativity. The task of modern socialism is not to ignore or dismiss the ECP, but to transcend it: to transform the measure of value from a weapon of exploitation into an instrument of emancipation.

Section I. The Economic Calculation Problem: Capitalist Framing

The Economic Calculation Problem emerged from a moment of crisis within capitalism itself. In 1920, as revolution spread across Europe in the wake of the Russian Revolution, Ludwig von Mises sought to disarm the socialist movement by declaring its project not just flawed but logically impossible. His argument hinged on the role of prices in coordinating production. In a capitalist system, producers exchange goods and inputs as privately owned commodities, and this process generates market prices. These prices, in turn, serve as a universal yardstick: they allow the capitalist to decide whether it is cheaper to build a bridge from steel or concrete, to expand a factory or import machinery, to employ one technique rather than another. The “miracle” of markets, for Mises, was that such comparisons happened spontaneously through the decentralized interactions of millions of owners.

Without private ownership of the means of production, Mises claimed, such exchanges would vanish. If all inputs belong to society, there can be no buying and selling of capital goods, and thus no prices to guide decision-making. A socialist planner may know the technical details of steel, wood, and concrete, but lacking a common denominator, he cannot judge their relative costs. To Mises, any attempt at planning without markets was like “groping in the dark”: a hopeless effort to compare the incomparable. This was the heart of the ECP, the assertion that private property was not just an economic arrangement but the very precondition of rationality.

This argument was sharpened and extended by Friedrich Hayek. Where Mises emphasized calculation, Hayek emphasized knowledge. In his 1945 essay “The Use of Knowledge in Society,” Hayek argued that markets do not merely calculate; they communicate information that is otherwise dispersed across millions of individuals. No central planner, however intelligent, could gather and process all the local, tacit, and constantly changing knowledge of society. Only markets, he claimed, could condense this scattered knowledge into a single signal: the price. For Hayek, the price system was an evolutionary discovery, a spontaneous order that surpassed the capacity of any designed plan. Attempts to replace it with conscious coordination would, he believed, necessarily lead to waste, inefficiency, and authoritarian control.

Together, Mises and Hayek’s framing of the ECP became one of the most powerful ideological weapons of the 20th century. Their critique went beyond economics into ontology: it declared that socialism violated the very conditions of human knowledge and rationality. From Cold War economists to neoliberal policymakers, the ECP has been invoked as proof that central planning leads inexorably to disaster, while markets embody freedom and efficiency.

But embedded in their argument is a profound ideological sleight of hand. Mises and Hayek treat the historically specific forms of capitalism, private property, competitive exchange, and market prices as transhistorical necessities. They mistake the phenomenal form (price) for the essence (social labor), and they conflate the limitations of 20th-century planning with the impossibility of socialism itself. By doing so, they elevate the market from a contingent institution of class society into a metaphysical principle of reason itself. The ECP, in its capitalist framing, thus serves less as a scientific claim and more as a defense of the bourgeois order. It naturalizes exploitation by presenting capitalist calculation as synonymous with human calculation.

Section II. Marxist Reinterpretation of the Problem

If the bourgeois economists are correct about one thing, it is that socialism cannot simply wish away the challenge of calculation. A society without rational methods of comparison would indeed descend into inefficiency and waste. But Mises and Hayek erred in identifying the source of rationality with private property and markets. Their argument rests on a fundamental confusion: mistaking the appearance of value for its essence.

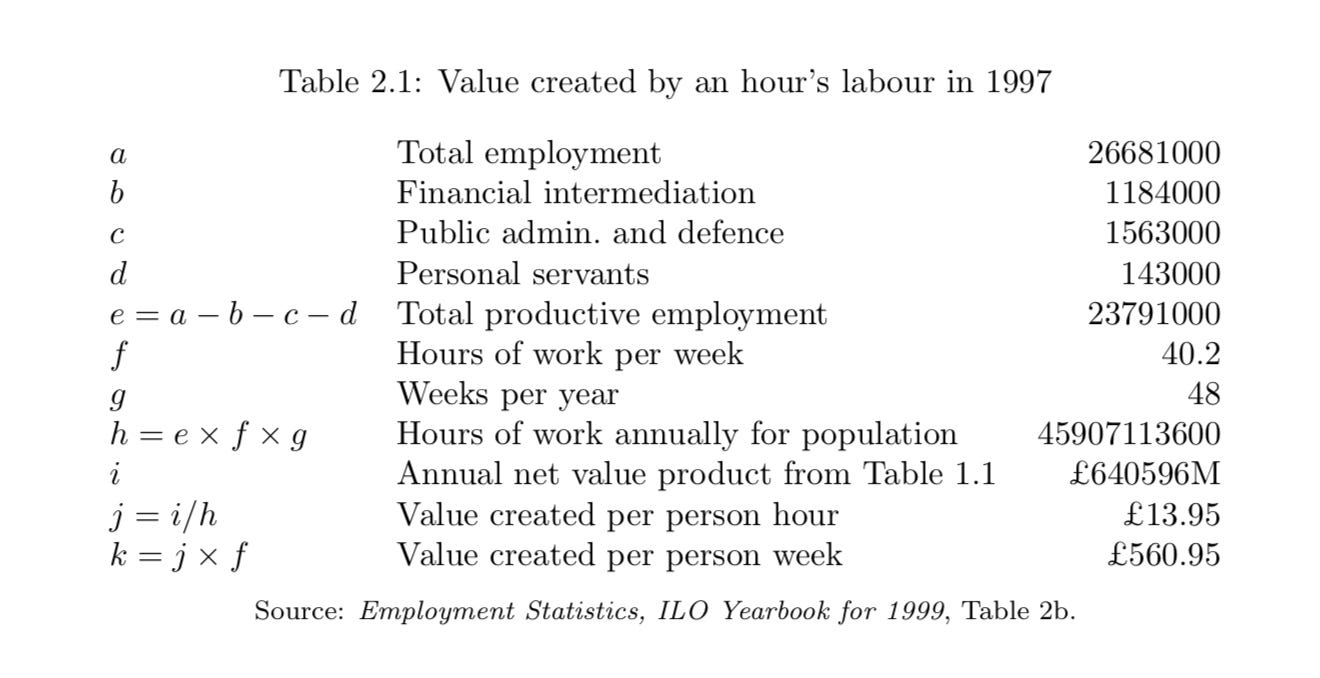

Marx demonstrated that the real substance of value is socially necessary labor time (SNLT). In capitalism, prices express this substance only in a distorted, fetishized form, mediated through competition, profit, and exploitation. The market does not create rationality; it merely reflects, in a chaotic and antagonistic way, the underlying reality that all production rests on human labor. To conflate the market’s price signals with rationality itself is to confuse the shadow for the substance.

From this perspective, the Economic Calculation Problem is not a universal refutation of socialism but the exposure of an unresolved contradiction within historical attempts at planning. The Soviet Union, for instance, sought to abolish private property and markets, but it did not succeed in developing a new, scientifically grounded system of calculation to replace them. Prices were set administratively, often arbitrarily, without being systematically linked to actual labor inputs or technical coefficients. The result was “imaginary prices”, numbers that bore no necessary relation to social labor or material reality. Planning devolved into bargaining between ministries, bureaucratic guesswork, and fulfillment of quotas on paper rather than in practice.

Here, the ECP seems vindicated: socialist planning appeared irrational, disconnected from reality, “groping in the dark.” But from a Marxist perspective, this was not because socialism abolished private property; it was because socialism had not yet completed the dialectical task of sublating capitalist value relations into a higher form of social coordination. The commodity form lingered; labor remained alienated; producers were excluded from direct participation in planning. In short, the transition was incomplete.

The true answer to the ECP, then, lies in returning to Marx’s core insight: calculation must be grounded directly in labor-time and material inputs, rather than mediated through the anarchic dance of the market. What markets achieve in a distorted way, through the clash of competing capitals, socialist planning can achieve consciously, scientifically, and democratically. Calculation is not impossible without markets; it is simply a question of building the right tools, institutions, and relations of production.

This reframing turns the ECP on its head. Mises treated the absence of private property as a dead end; Marxism reveals it as an opportunity for liberation. Where capitalists rely on exploitation and competition to produce rough approximations of value, socialism can develop a system of direct, transparent, and rational coordination, one that measures production in terms of human labor and social need rather than profit. Far from being irrational, such a system would surpass the market in precision and efficiency, because it would be freed from the distortions of exploitation and the blind pursuit of profit.

Thus, the Marxist reinterpretation does not deny the ECP but transcends it dialectically. It accepts the problem as real but insists the solution lies not in retreating to markets, nor in clinging to rigid command systems, but in developing new forms of calculation rooted in labor and collective control. Only by uniting technical rationality with proletarian power can socialism fulfill its promise and silence the critique that has haunted it since 1920.

Section III. Historical Lessons

The abstract debate over the Economic Calculation Problem becomes clearer when tested against the history of actually existing socialist projects. The experiences of the Soviet Union, Chile under Allende, and China under Deng Xiaoping each reveal different dimensions of the problem and the possibilities for its resolution.

1. The Soviet Union: Arbitrary Prices and Bureaucratic Bottlenecks

The USSR’s rise was extraordinary: in a few decades, it transformed from a largely agrarian society into a global industrial superpower. Yet this achievement came with structural weaknesses. Soviet planners abolished markets for capital goods but replaced them with administrative pricing. Ministries fixed the costs of steel, oil, tractors, or machinery by decree, often with little reference to actual labor inputs or technological efficiency. Over time, these prices became fictitious numbers, disconnected from the material realities of production. Enterprises fulfilled plan targets “on paper” while real inefficiencies accumulated: overproduction of some goods, shortages of others, and systemic waste.

In this sense, Mises’ critique had bite. Soviet planners were indeed “groping in the dark,” not because planning is impossible, but because they lacked a genuine unit of calculation. Without grounding prices in socially necessary labor-time or material coefficients, the Soviet economy drifted into dysfunction. Moreover, bureaucratic hierarchy excluded workers from participating in planning, creating a new administrative class whose interests diverged from the proletariat. The collapse of the USSR was thus not the “proof” of the ECP but the outcome of an incomplete socialist transition, where the value-form and alienated labor persisted under a bureaucratic guise.

2. Chile’s Cybersyn: A Glimpse of Socialist Cybernetics

In the early 1970s, Chile under Salvador Allende attempted something radically new: Project Cybersyn, a cybernetic planning system designed by Stafford Beer. Using telex machines, real-time data, and feedback loops, Cybersyn aimed to give workers and planners a dynamic picture of the economy. Rather than relying on static quotas, the system could adapt to changing conditions, balancing supply and demand in real time.

Although the project was cut short by Pinochet’s US-backed coup in 1973, Cybersyn remains proof that modern technology can overcome the ECP’s challenge. Mises assumed that no central system could process dispersed information, but cybernetics and networked feedback showed otherwise. Had it been allowed to mature, Chile’s experiment might have pioneered a democratic, adaptive alternative to both markets and rigid command planning.

3. China’s Reforms: Market Tools within Socialist Strategy

China offers a third lesson. After Mao, Deng Xiaoping introduced the concept of a “socialist market economy.” Far from a betrayal of socialism, Deng argued that markets could be used as tools under the guidance of proletarian state power. In practice, this meant reintroducing market exchange for consumer goods and enterprises, while the state retained control over land, banks, and strategic industries.

Critics called this “capitalism,” but Deng’s reforms can also be read as a dialectical response to the ECP. By temporarily reintroducing market prices, China secured a comparative metric of efficiency while maintaining overall socialist direction. Today, China has gone further: experimenting with AI logistics, digital currency, and data-driven governance, tools that echo the aspirations of Cybersyn but at a planetary scale. Whether this synthesis represents a transitional form toward communism or a new variety of state capitalism remains debated. What is clear is that China demonstrates the flexibility of socialist calculation when combined with technological development and strategic class power.

Taken together, these historical cases show that the ECP is not an abstract law but a challenge whose resolution depends on concrete institutions, class dynamics, and technological tools. The Soviet Union’s failures highlight the danger of arbitrary calculation; Chile’s experiment reveals the potential of cybernetics; and China demonstrates how market mechanisms can be subordinated to socialist aims. Each contributes to a dialectical understanding: the ECP is neither an insurmountable barrier nor a trivial concern, but a contradiction that must be addressed if socialism is to advance.

Section IV. Contemporary Socialist Calculation: Beyond ECP

The challenge posed by the Economic Calculation Problem is real, but it is not eternal. The 20th century showed us both the limitations of bureaucratic planning and the dangers of fetishizing markets. The 21st century offers us something new: the ability to calculate, coordinate, and plan production with tools that neither Mises nor Marx could have imagined. The ECP thus becomes not a permanent obstacle but a dialectical contradiction, overcome through new institutions of labor, technology, and democratic control.

Labor Vouchers: A Transitional Unit of Account

Marx himself anticipated the problem of distribution under socialism. In his Critique of the Gotha Program, he suggested labor vouchers: certificates issued to workers corresponding to the amount of labor they contributed. Unlike money, these vouchers could not be hoarded or speculated upon; they were simply claims on a portion of the social product. This system grounds calculation directly in socially necessary labor time, avoiding both arbitrary bureaucratic numbers and the mystification of market prices. While transitional, labor vouchers provide a rational measure of value in the early stages of socialism, before full communism abolishes value relations altogether.

Input–Output Analysis: Mapping the Material Flows

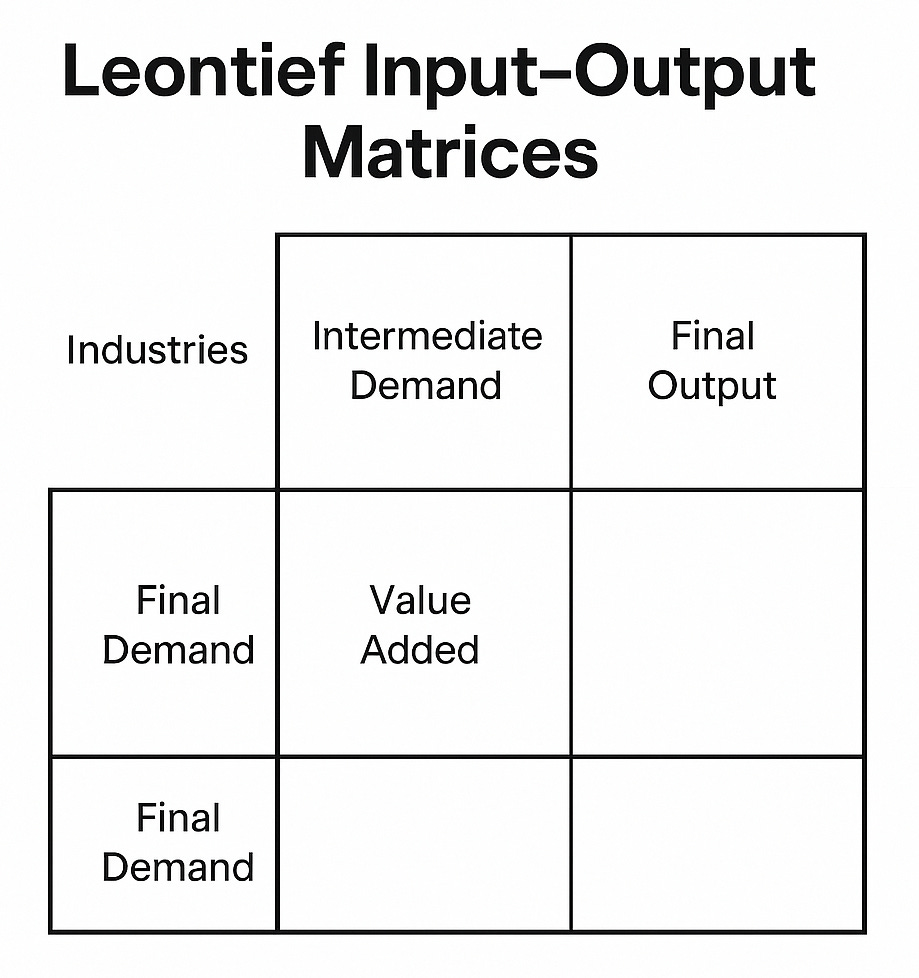

In the mid-20th century, Wassily Leontief pioneered input–output analysis, a mathematical technique that maps how every sector of the economy depends on every other. This framework reveals the interdependencies of production: how much steel is required for tractors, how much energy is required for steel, how much coal for energy, and so on. By tracing these flows, planners can model the economy as a system of equations and optimize allocation without market exchange. In effect, input–output tables make visible what markets conceal: the material and labor requirements that underlie every commodity. For socialist planning, they provide the skeleton of a calculation system rooted in real technical coefficients rather than fictitious prices.

Cybernetics and AI: Real-Time Socialist Coordination

Where Mises saw impossibility and Hayek saw chaos, modern technology offers cybernetic feedback systems that make rational planning feasible on a vast scale. Project Cybersyn in Chile hinted at this potential with telex machines; today, with global digital networks, artificial intelligence, and cloud computing, the possibilities are exponentially greater. Supply chains, energy grids, and transportation systems can be modeled and adjusted in real time. AI can optimize routes, balance resources, and forecast demand dynamically. Crucially, these technologies need not remain in the hands of corporations; under socialism, they can be appropriated as instruments of collective intelligence, embedding democratic participation into the very circuits of planning.

Ecological Planning: Beyond Profit Toward Sustainability

Perhaps the most urgent task of socialist calculation in our century is ecology. Capitalist markets treat nature as a gift, externalizing costs onto ecosystems and future generations. The result is a climate catastrophe, mass extinction, and planetary instability. A socialist system of calculation must internalize these costs, not as prices in a carbon market, but as material constraints integrated into planning. Labor-time accounting must be supplemented by ecological accounting, ensuring that the reproduction of human society does not rupture the metabolism of nature. Here, Marx’s analysis of the “metabolic rift” becomes central: rational planning means planning not only for efficiency but for the preservation of life itself.

In sum, contemporary socialism can address the ECP not by denying it, but by surpassing it. Labor vouchers provide a rational unit of account, input–output analysis reveals the interdependence of production, cybernetics, and AI enable real-time coordination, and ecological metrics ensure sustainability. Together, these tools constitute a new architecture of socialist calculation, a system more transparent, adaptive, and humane than anything markets or bureaucracies can offer.

Section V. Political Dimensions: Calculation and Class Power

The debate around the Economic Calculation Problem often disguises itself as a purely technical question: can planners acquire enough information to replace markets? Can algorithms substitute for prices? Can labor-time or input–output matrices solve the riddle of efficiency? Yet to treat the ECP only as a question of information is to fall into the same error as Mises and Hayek. Calculation is not merely a matter of numbers; it is a matter of class power.

The Soviet Union’s experience illustrates this most starkly. Even if it had perfected its accounting methods, the persistence of a bureaucratic elite undermined the socialist project from within. Workers were excluded from genuine participation in planning, and production was dictated by ministries and administrators rather than by the associated producers themselves. This gave rise to what many Marxists described as a bureaucratic class: a stratum that monopolized control over the means of coordination while living off the surplus generated by the proletariat. In effect, calculation became alienated, performed over and above the workers rather than by and for them. No algorithm could rescue such a system from its contradictions, because the root problem was not technical but social: the reproduction of alienation and hierarchy under a socialist façade.

This insight directs us to a crucial conclusion: socialist calculation must be inseparable from proletarian democracy. Technologies like labor vouchers, input–output analysis, or AI-driven logistics are powerful tools, but their emancipatory potential depends entirely on who wields them. If they are deployed by a bureaucratic elite, they risk becoming instruments of domination, new means of surveillance, control, and extraction. If they are embedded in democratic institutions of workers’ councils, syndicates, and assemblies, they become tools of liberation, ways for the associated producers to consciously regulate their collective labor.

The lesson is clear: socialism cannot be reduced to technical efficiency. Capitalism itself is brutally efficient in extracting surplus and destroying the planet. The real measure of socialist calculation is not whether it “works” in the abstract, but whether it abolishes alienation, empowers the working class, and orients production toward human need and ecological balance. Efficiency must serve emancipation.

This political dimension also addresses Hayek’s critique of “knowledge dispersion.” Hayek was right to observe that no central planner can possess all the tacit knowledge of society. But his conclusion, that only markets can coordinate this knowledge, ignores a third possibility: distributed, participatory planning. By embedding workers themselves into the planning process, through councils, digital platforms, and cybernetic feedback loops, the dispersed knowledge of society is not lost but directly mobilized. Rather than prices as distorted signals, producers themselves become conscious participants in the circulation of information. The contradiction of dispersed knowledge is resolved not through markets, but through democracy.

In this light, the ECP is not just an economic debate; it is a class struggle in disguise. Mises and Hayek naturalized capitalist calculation to defend bourgeois power; bureaucratic planning reproduced alienation by disempowering workers, but socialist calculation, properly understood, is the conscious mastery of production by the associated producers themselves. Only when the technical and political dimensions are united can the problem be resolved. The solution to the ECP is not simply better numbers; it is the abolition of alienation through proletarian control of calculation itself.

Conclusion: Dialectical Synthesis for the 21st Century

The Economic Calculation Problem has haunted socialism for more than a century. First raised by Mises and sharpened by Hayek, it was meant as a final word: the claim that socialism is not merely inefficient but impossible. And yet, history itself refutes their absolutism. Planned economies industrialized nations in decades, defeated fascism, and demonstrated the immense power of collective coordination. Socialist experiments have stumbled, failed, or been overthrown, but not because calculation is impossible. They fell because the task of sublating capitalist value relations into a higher form of socialist calculation remained incomplete.

The truth revealed by history is that the ECP is neither an iron law of impossibility nor a trivial obstacle. It is a contradiction, one that reflects the unfinished dialectic of socialism. The bourgeois economists were right that arbitrary command systems collapse into dysfunction; they were wrong to conclude that private property and markets are eternal. The answer lies in transcending both the chaos of markets and the rigidity of bureaucratic planning through a new synthesis of labor, technology, and democracy.

Today, socialism possesses tools that earlier generations could only dream of:

Labor vouchers that directly measure social contribution.

Input–output analysis to model the interdependence of production.

Cybernetic planning and AI for real-time feedback and optimization.

Ecological accounting to repair the metabolic rift and secure planetary sustainability.

These are not utopian fantasies but concrete possibilities. What Mises deemed impossible is today a matter of design and will. But the decisive question remains political: who controls these tools? In the hands of a bureaucratic elite, they become new chains; in the hands of the associated producers, they become instruments of liberation.

The ECP thus forces us to recognize that socialism is not just a technical alternative to capitalism but a qualitative rupture with it. Capitalist calculation is rooted in exploitation, profit, and alienation; socialist calculation must be rooted in labor, need, and freedom. Capitalist rationality produces ecological collapse and human misery; socialist rationality must measure success in terms of human flourishing and ecological balance. The contradiction posed by Mises is resolved not by retreat, but by revolution.

We therefore return to the dialectical principle: every negation contains the seed of a higher affirmation. The ECP, once posed as a weapon against socialism, becomes its proving ground. In confronting it directly, socialism discovers its task: to transform calculation from the blind compulsion of the market into the conscious self-organization of humanity. The measure of value, once a tool of exploitation, becomes a measure of emancipation.

In the 21st century, the challenge is not whether socialism can calculate, but whether humanity can afford to leave calculation in the hands of capital any longer. As ecological crisis deepens and capitalist markets drive us toward catastrophe, the necessity of rational, democratic, and ecological planning is no longer a theoretical debate but a question of survival. Socialism, armed with the tools of labor-time, cybernetics, and proletarian democracy, is uniquely positioned to answer that question.

The task ahead is clear: to build a world where calculation serves life rather than profit, where labor serves liberation rather than alienation, and where humanity, at last, becomes the conscious architect of its own destiny. That is the dialectical resolution of the Economic Calculation Problem. That is socialism’s promise in our century.

As society progresses, capitalism becomes increasingly inefficient, and socialism becomes not just superior, but inevitable. Modern computation has the potential to solve value with far more accuracy than free markets ever could, sidestepping speculation, supply manipulation, "greedflation", etc. All while accounting for externalities.

Very insightful